Oct 27, 2014. Competitive advantage does not mean a company earns high returns on capital just because the management is smart. It means that competitors are not able to match its returns on investment. There may be a barrier to market entry, or switching costs for customers are relatively high. The company with competitive advantage can sell its goods at prices well above its cost of sales, without fear that competitors will flood the market and attempt to undersell it. This is reflected in healthy gross margin that is sustained over an extended time, and steady or increasing returns on capital investment.

In the metaphorical toll bridge investment, customers must pay to use the company’s product in order to obtain something they demand. In the literal example of a toll bridge, customers must pay for access to the bridge to a destination. Assuming the demand to reach that destination is persistent enough to justify building the unique bridge, the shares of the company are bid up because of the durability of this demand. The problem with toll bridge investments is that unless demand to reach that destination continues to increase, the company shares will not continue to rise over time. Since the company management recognizes this, it will likely pay a dividend in order to keep investors, as long as earnings continue to support it. Assuming there is no alternative bridge, the company’s competitive position is hard to attack, and management does not have to be world class. Earnings do not rise any faster than economic growth at the bridge destination, the stock price will reflect this. In an attempt to increase earnings more quickly, Management may allocate some income to attempted expansion into other markets, but there it does not possess a competitive advantage and will do no better and possibly worse than competitors who are dominant in those different areas. An example of this is Hawaiian Electric (HE), a regulated electric utility that supplies virtually all power on the Hawaiian Islands. Its growth is limited to the growth of power demand on the Islands.

What if over time demand for reaching the destination not only increased with growth of the most stable economies in the world, but also with the growth of the most rapidly growing economies (thus growing at a rate exceeding the average growth of the world GDP)?

What if the company had exclusive use of 2 toll bridges, with different markets clamoring for access to them? What if the management in fact did not merely rely on the advantaged position afforded by their non-reproducible franchise, but was driven by a historic struggle for economic survival to run the most cost efficient toll bridge possible, therefore focusing its capital allocation on improving its transportation speed and the capacity of its bridges? What if management was systematically incentivized to grow return on invested capital, earnings, free cash flow, and expected to purchase ownership in the company?

What if the toll bridge investment was Canadian National Railway (CNI)?

CN is one of 7 Class I (Freight) railroads remaining in North America (in 1900 there were 132): BNSF Railway, Canadian National Railway, Canadian Pacific Railway, CSX Transportation, Kansas City Southern Railway, Norfolk Southern Railway, Union Pacific Railroad.

The CN network is a relatively scarce resource. CN in its current state is a product of approximately a century of transitions to and from government control, mergers and bankruptcies. In the second half of the 20th century successive CN leaders strove to reduce extent of railway track, increase efficiency, and institute technical and labor modernization. As a result, the profitability of the railway materially improved while the railway assets became much scarcer and therefore more indispensable to the customer, hence the emergence of the toll bridge investment scenario. While railroad has the lowest cost of land transport to customers, CNI is subject to relatively limited competition because of the limited extent of existing railroads, and the fact that new railroads will not be built because of expense and right of way issues.

The CN network is advantaged by its specific geographic range.

By late 1990s (CNI went public in 1995 as the largest privatization in Canadian Government history), CN leadership had built the distinctive Y shaped map of CN rails. This stretches from the Port of Prince Rupert on the Pacific Coast, and Port of Halifax on the Atlantic, through Chicago, the transportation hub of North America, and down to the Gulf Coast at New Orleans. Because of a 1998 alliance with Kansas City Southern Railway Company (KCSR), customers can ship from Chicago though out the KCSR network south to Missouri, Oklahoma, Mississippi, Texas, and to Mexico’s largest railway system, Transportacion Ferroviaria Mexicana, S.A. de C.V. which has a separate alliance with KCSR.

Finally In 2008 CN acquired most of the Elgin, Joliet & Eastern Railway Company (EJ&E) around Chicago. This allows CN to avoid severe rail congestion in the Chicago hub which afflicts other Class I railroads in the area. Reportedly previously it sometimes took as long to get through Chicago’s 30-mile hub as it did to get there from Winnipeg.

CN rail has exclusive access to ports on the Pacific (Port of Prince Rupert) and Atlantic (Port of Halifax), moreover these ports are privileged in their location.

Although Port of Prince Rupert and Port of Halifax do not have the highest traffic in North America, they rely on CN exclusively for rail link. Because of its location on the Northwestern coast of Canada, Prince Rupert is closer to Asia than any other North American port by up to 58 hours. It has the deepest natural harbor depths on the continent. This allows usage by the very largest and most modern container ships, super post-Panamax cargo ships. It has little traffic congestion, and this makes it increasingly attractive to shippers compared to congested ports on the U.S. Pacific coast.

Container traffic was added to bulk commodities in 2007 with the first dedicated intermodal (ship to rail) container terminal in North America. Currently Prince Rupert is expanding the number of super post-Panamax cranes to 8, and adding train tracks. According to the Prince Rupert Port Authority, surging Asian trade is projected to increase container volumes by 300% into North America by 2020. The planned expansion will expand the container capacity of the terminal from 0.75 to 2 million TEUs, making it the second largest handling facility on the West Coast. CN Rail is the only way to take cargo in or out of Port of Prince Rupert.

Development and modernization of the container terminal is funded mostly by Canadian Federal and Provincial Government and Prince Rupert Port Authority; while CNI has paid only a fraction of costs, for rail related development. Development of this port directly promotes CN revenue but CN pays only a fraction of the required capital investment.

Port of Halifax on the Atlantic coast is the deepest, wide, ice-free harbor (with minimal tides) on the North American Atlantic Coast and is two days closer to Europe and one day closer to Southeast Asia (via the Suez Canal) than any other North American East Coast port. It is 3 days faster from Rotterdam than NY harbor, 2 days faster from Singapore to NY via Suez Canal. In addition, it is one of just a few eastern seaboard ports able to accommodate and service fully laden post-Panamax container ships using the latest technology and world class security.

The Halifax Port Authority has invested over $100 million over the past three year on infrastructure and efficiency improvements.

Unlike Port of Prince Rupert, cargo volume at Port of Halifax is not growing steadily yet since the recession nadir in 2009. 9.6M metric tonnes in 2009, 8.6 M metric tonnes in 2013. Again, the absence of congestion here compared with more southerly ports bodes well for future traffic loads, all to be carried exclusively by CN, when the global economy finally recovers from the effects of the Great Recession.

Management at CNI is a product of a century long struggle to increase efficiency and profitability and this tradition is carried on today.

For decades in the second half of the 20th Century, A succession of company Presidents fought to build a more efficient railroad which could fulfil its potential and be profitable even though it was controlled indirectly by the Canadian Government and therefore treated by its directors as a tool for political or development goals rather than a business.

When CN acquired Illinois Central Railroad in 1998 in order to add the network extension down through Chicago, it recruited Hunter Harrison, former head of Illinois Central, who took control of day to day operations as COO. A veteran railroad man, Harrison was credited with drastically improving efficiency by implementing “scheduled railroading,” whereby freight trains were operated on a more controlled schedule designed for efficiency. CN became a scheduled railway, increasing utilization of locomotives, freight cars, and train crews. Previously, Illinois Central had the lowest operation ratio* in North American railroads, this title soon passed to CN.

Harrison’s recruitment into CN leadership (he became CEO in 2003) is part of a long preoccupation at CN with improving the company’s efficiency and agility as a railway business. It is this culture which drives CN to continue achieving record margins and efficiency even after having seemingly won the fight against competition. An interesting place to view this culture of obsession with efficiency is the Management Information Circular and Notice of Annual Meeting of Shareholders of April 2014. Here we see that CNI aligns management compensation with corporate value creation and profitability.

Because of the advantaged competitive situation of toll bridge assets, management can become complacent because the indispensable nature of the company services means it is relatively protected against competition for the foreseeable future. In the case of CNI, an overview of non-employee management compensation reveals a focus on rewarding behavior that tangibly increases returns on investment for the company’s capital investment and in turn shareholders.

For example, 70% of the annual incentive bonus is based on attainment of performance objectives: Revenues (25%), Operating Income (25%), Diluted Earnings per Share (15%), Free Cash Flow (20%), Return on Invested Capital (15%).

Individual performance contributes 30% of the incentive bonus. This is scored based on attainment of personal business-oriented goals considered to be the strategic and operational priorities related to each executive’s respective function, with a strong overall focus on: balancing operational and service excellence, delivering superior growth, opening new markets with breakthrough opportunities, deepening employee engagement and stakeholder engagement.

Long-term incentives include Performance Share Units, PSU, and conventional stock options. PSU are company shares which vest conditional to the attainment of target ROIC and target increase in share price over a 3-year performance period. Stock options granted in the same proportion as PSUs, vest over 4 years.

CNI requires management to invest in the company on the same terms as every other investor. CN specifies minimum required stock ownership by management, to be attained with 5 years from onboarding and then maintained. Stock ownership must be purchased on the open market, or using PSUs or deferred bonuses and held until retirement. Stock options do not count towards share ownership requirements.

All management subject to the plan exceeded their share ownership requirement at the end of 2013. CEO Claude Mongeau held over 25x his base salary in shares, and his requirement was 5x his base salary.

CNI suffers minimal compensation related stock dilution, and maintains a strong rate of stock buyback. As of 2013, about 7.6 million shares are to be issued under exercise of options, less than 1 % of the outstanding shares on the market. In 2004 there were 1159 million shares on the market, in 2013 there were 834 m shares, a reduction of approximately 28%. There are no preferred shares. CN has one class of stock. Management own the same stock and have similar voting power as myself or other shareholders.

In sum, not only does CN possess assets which will not be duplicated, and a very strong barrier to competition, but in addition management is incentivized to make these assets work profitably for shareholders. This results in a synergistically beneficial effect on returns on investment for the company and shareholders.

Financial results and valuation

CNI 3rd quarter 2014 earnings of C$1.04 missed analyst estimates by C$0.01, and revenue of C$3.12B (15.6% increase) missed by C$30M. The headlines might equally as justly have read: “analysts inaccurately estimated CN earnings”. I do not think of quarterly earnings as a reason to make buy/sell decisions. However the earnings call contained some items that illustrate the strengths of CN.

CN is growing much faster than GDP growth. This is expected since international trade increases in complexity and volume out of proportion to GDP growth. CN is in a secular growth market, moreover is not dependent on the health any specific industry.

Revenues and carloads (1.5 million) reached all-time records. International revenue increased close to 25% while domestic revenue was flat. International revenue was driven by Pacific Coast (Port of Prince Rupert) traffic, where emerging markets export to North America, with strong traffic into the US Midwest.

Operating ratio reached new record of 58.8%, continuing to be the lowest of all North American railroads. Incredibly, revenue ton miles, RTM, grew 15.4% at no incremental cost. These illustrate the unparalleled efficiency of CN rail.

Fuel costs shrank by 3%. CN plans to increase prices at least 3%, noting that North American rail capacity remains “snug”. CN is able to raise prices fundamentally because of its economic moat. Management is incentivized to continue attempting to shift service from lower to higher value cargo.

While the strong traffic drove increases expenses for labor, equipment leasing and costs including new locomotives and maintenance, these were significantly less than the increase in operating income of 19% and net earnings of 21%.

Some thoughts on performance in the past decade. Looking at revenue over 10 years from 2004 ($6.458 B) to 2013 ($10.575B), an increase of x1.61, we see a steady increase, except for a dip of approximately 15% from 2008 to 2009. This occurred in context of the Great Recession, so is not unexpected, railroad revenue is definitely related to GDP growth. The steady increase in revenue over a considerable time suggests CNI is dependable as a money maker. Net income rose from $1.259B to $2.612B, an increase of x2.07 outpacing revenue growth. Because of stock buy backs, diluted earnings per share increased from $1.08B in 2004 to $3.09B in 2013, an increase of 2.86x or 18.6% per year. Free cash flow increased from $1.069B in 2004 to $1.575B in 2013, an increase of 1.47.

CNI generated free cash flow of $1.575B in 2013, with FCF/sales of 14.89%. The lowest such ratio in 10 years was 7.16% in 2008. The lowest ROIC in the last 10 years was in 2004 at 10.59%, the highest was in 2012 at 16.66%. Gross margin hit 84.7% in 2013.

Valuation. While CNI possesses unquestionably valuable assets and franchise, its stock has been bid up in recent years. The cash return measure of valuation tells how much free cash a company generates from its capital, both equity and debt (cash return is FCF plus interest expense divided by enterprise value. Enterprise value is market cap, plus debt, minus cash, that is, cost of the company to a private buyer). For CNI, cash return is 2.8%, not impressive.

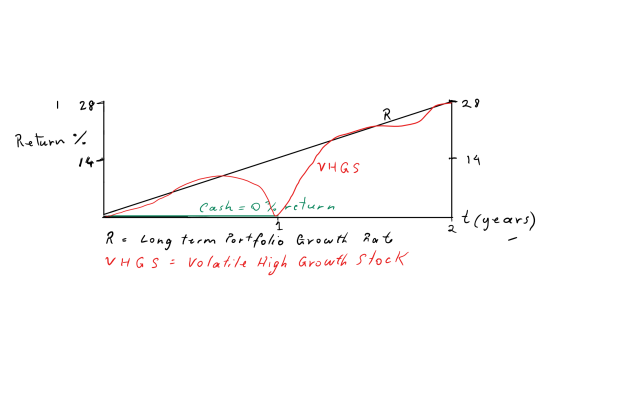

Buy decision. The investment worthy qualities of CN Rail, a wonderful business with a wide economic moat, excellent management respectful of shareholders, have been put in place in approximately the last 10 years or more. Growth in trade with emerging countries will maintain a secular bull market for CN services for the foreseeable future. As this has been recognized by investors and the media, the stock price has increased at a rate of growth greater than earnings over that time. The stock price increased from 12.4 on October 2 2004 to about 70 on October 1 2014, an increase of 5.6 times, while earnings per share increased approximately 2.86 times. The lowest PE in the last 10 years was 8 in 2009 (10 years earlier in 1998 it was less than 4), currently it is almost 23, the highest ever.

This is a case of a good business with sound prospects that has become expensive relative to its past prices. Investing depends partly on what the future holds, and in judging what to expect here, there are a few variables to consider. First, will the quality of the business change? CN Rail has a wide moat and it is unlikely this will change for the foreseeable future. Second, will investors continue to admire the prospects? Media and investor sentiment can be affected by factors that do not tangibly change the company. If there is a change in investor sentiment caused by global events which do not actually reduce CN traffic or ability to price profitably, the stock price might drop and result in a buying opportunity. Third, will the market for CN services actually change? Should a global event cause a tangible economic slowdown that reduces CN business, I think we can rest relatively assured that the recession will end, and CN will regain business after an interval. This again would create a buying opportunity for the patient investor. Fourth, will investor sentiment remain enthusiastic for CN? It is possible for popular companies with a recognized wide moat to stock prices that are expensive relative to the underlying business, for a prolonged period of time. However, this is not susceptible to prediction. The disadvantage of relying on this is that the stock price holds little margin of safety. However, if we ask the question, will CN earnings be significantly greater in 10 years than they are now? I think the answer is unquestionably “Yes”.

Performing a simple DCF analysis using current EPS $3.09, growth rate of 18% for 10 years, terminal growth rate 3% for 10 years, discount rate 8$, discounted share price is $99.95. Using an EPS growth rate of 9%, discounted share price is $58.86.

It might be reasonable to place a relatively small stake on a highly priced business with good prospects. Otherwise, one might wait, study and learn about the business, building confidence in the value of the business that will enable one to buy with appropriate commitment in the face of future market downturns.

Summary

CN Rail reveal evidence of durable competitive advantage, with outstanding gross margin, as well as operating ratio, good return on investment measures, growing free cash flow. Management is incentivized to maintain the ability of the company to obtain outstanding returns on investment, and respects shareholder interests. CN Rail manages assets that are unique and indispensable, for which CNI does not pay all the cost of capital investment. Moreover, the market for CNI services produces with these assets is growing inexorably, with no damaging competition perceptible on the horizon. Unfortunately, CN’s top of class status is well recognized by the market and shares have been bid up, to all time high PE levels, so it no longer affords a bargain price.

*Operating Ratio: the yardstick of railroad profitability, equal to operating expenses as a percentage of revenue.