In the market volatility in September 2015 and January 2016, the S&P fell 10% from its peak of 2126 on July 17 2015 to 1921 on September 4, 2015, before climbing again to a peak of 2099 in November 6, then falling 12% to 1864 on February 12, 2016. I did not have a source of cash with which to take advantage of some really attractive bottom prices in stocks, specifically ADBE. I resolved to find a way to take advantage of the low prices which appear in market dips, as purchases made in teeth of market terror are key to producing the most outstanding returns.

The purchase additional stocks for the portfolio must be funded either from the sale of current holdings or from cash kept for the purpose (I do not consider the use of debt to be a sound option).

There are various arguments against the sale of current holdings to simultaneously fund new purchases. The decision to buy is driven by the identification of a prospective purchase that is currently found at an attractive, low price, or where business prospects for the company appear to be more promising in the immediate future. Meanwhile, to optimize return, the company that is sold to fund the purchase would be judged to have less promising prospects and hence likely to fall in price, either because it is currently judged to be overvalued, or because business prospects appear uncertain in the near future. But there is no particular reason that the advent of an attractively low price in the target purchase would coincide in time with an attractively high selling price in another holding. Rather, one may be faced with the prospect of selling a stock at a merely reasonable price to enable the purchase of a stock which is found to be hopefully at a nadir. Unfortunately, the decision can potentially be wrong on both sides, that is, the price of the target purchase may subsequently fall even more, while the sold stock may subsequently continue to rise.

A variation of this strategy is to sell a stock that seems overvalued, or is expected to fall in stock price, in order to build up a cash reserve to fund purchases of a stock in the future, rather than simultaneously. The problem with this strategy is that it based as it is on prediction of the future, a sketchy enterprise at best.

Indeed, the problem with any approach based on predicting the future of stock prices is that stock prices do not necessarily reflect current business events in the company in question at all. They may rather reflect the market’s shifting reaction to those events, in turn driven by entirely distinct and distantly related social or economic forces. Because of this, a stock that seems overvalued, and thus a likely candidate for harvest, may continue to rise into regions of continued overvaluation if social or economic sentiment looks favorably upon it, against conventional rational business expectations. In this case, the sale price would be regretfully too low, too soon. Or in fact one may decide the stock should after all have been held for the long term. Conversely, the tide of market sentiment may tumble a stock even though the company is prosperous, producing regret that one did not harvest at the previous peak.

One characteristic of my investing approach is the attempt to recognize and understand the emotional currents underlying investing decisions. By doing so, one can steer a course that is free of emotional hazards to sound investing decisions. In the present case, awareness (perhaps not fully conscious) of the shakiness of one’s predictions about future prices is likely to cause anxiety which interferes with rational trading decisions.

One cannot change a future outcome that one does not control, either before it happens, or after it has happened. But since no one else can either, failure to do so does not impair one’s performance relative to other investors, that is, relative to the market. What one can do is first, avoid the chances of making an error, while maximizing the chances of better results, and second, minimize the emotional influences which interfere with sound investing decisions.

A different strategy is to build up cash reserves to fund stock purchase. In the absence of new cash, the only possible source of these is stock dividends credited to cash instead of reinvested. These have a few advantages as a source of cash. First, the cash is contributed regularly, at a range of different stock prices, so that no bet is made that a particular price would have been the optimal selling price. Thus, one avoids the chance of making a large error in choosing a sale price which may turn out later to have been the wrong one. no specific decision must be made to sell a treasured holding, with the accompanying distress. This will minimize the emotional turmoil which leads to hasty, ill thought out decisions.

There are thoughts pro and con this strategy. Crediting dividends to cash means they will not participate in the hopefully continued rise in the stocks they were contributed from. In order to make this strategy worthwhile, one needs to buy new investments at a low enough price, or to achieve a high enough return on investment, so that this will compensate for the time of missed returns before the cash was invested.

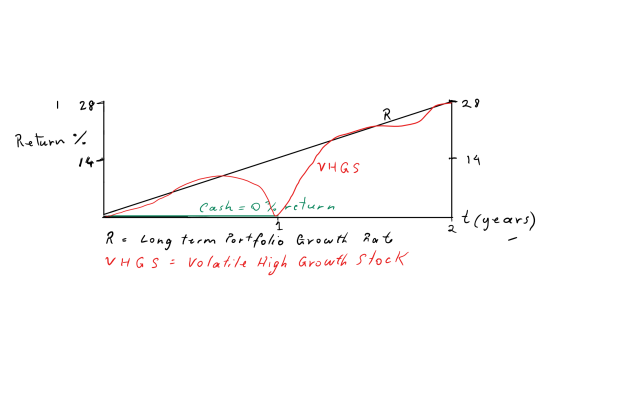

Purchasing at a discount from the long term stock growth rate is crucial to maximize the chance of a good outcome. If the stock fits criteria for the portfolio, none of which depend on short term market action, then its long term growth rate should approximate that of the portfolio. The cash that is held pending the new stock purchase has a return of 0%. Let us assume that the stock to be purchased would have a certain price at the time of purchase, if the stock was adhering continually to the long term portfolio growth rate ( R ), and call this P (r). Let us assume that at the time of purchase, the stock has fallen so that it is discounted in price P (r). In order for the cash invested in the new purchase to attain the portfolio ( R ), then the discount from P (r) at which the new stock must be purchased must equal the time the cash was held, in years, t (cash), multiplied by ( R ). The illustration below shows this for a stock bought with cash that has been held for one year.

For cash held for less than a year, then the discount from P (r) would need to be relatively less, while still enabling the stock to attain the same portfolio ( R ). One source of error in purchasing stocks, especially volatile high growth stocks, is failing to patiently wait for an adequately low price. In my proposed strategy of using accumulating cashed dividends to fund new stock purchases, the fact that the cash balance builds up slowly as dividends are contributed, is an incentive to wait for an adequately low price so as to generate returns at least equal to ( R ). This is because frequently making small investments which use up the accumulating cash, if made at a discount to P (r) which is less than t (cash) times ( R ), will result in subpar long term returns.

There remains one question: if the stated goal of a rational policy of accumulating cashed dividends and reinvesting them, is to merely match the long term growth rate of the portfolio that would be attained if the dividends had been automatically reinvested in their respective stocks in the first place, then what is the point of hoarding the dividend cash in the first place?

The reason is as follows: some stocks seem to have a higher expected growth rate because of the strength of their business and market expansion. However once this is well recognized by the market, the stock in question becomes chronically highly priced, and is rarely available at an attractive price. However, these stocks can yield great returns if they can indeed be found cheaply. And, inevitably they sooner or later do fall in price. In fact, when a company from which the market has high expectations (ADBE), meets a setback, it is generally swiftly punished and its stock falls more than would be the case for a company with a solid business but from whom the market has more conventional expectations (Philip Morris International). This type of company might be termed a Volatile High Growth Stock. The above strategy of accumulating cashed dividends to take advantage of these infrequent opportunities can then in fact lead to overall increased returns.

Again the promise of higher returns by a high growth stock is only likely to be fulfilled if the purchase price is low enough. On this inarguable basis, a sound strategy might be to buy the target stock with half of the available cash when it reaches a % discount from the previous 52 week peak, that is equal to the 10 year growth rate for the portfolio ( R ). Should the target stock fall to 2 x ( R ) from the same previous peak price, then the remainder of available cash will be invested in it.

This strategy may not be perfect, for example it may result in only half of the available cash being invested in the target stock at an attractive price. On the other hand, it preserves the chance for purchase of at least some of the target stock at the truly great price of a 30% discount to previous peak. This approach should at least preserve the average portfolio growth rate from damage caused by ill-advised purchases. Meanwhile, If the target stock is one with growth rate relatively higher than the average for the portfolio, this should raise the portfolio performance.